How drivers and designers can reduce driver distraction

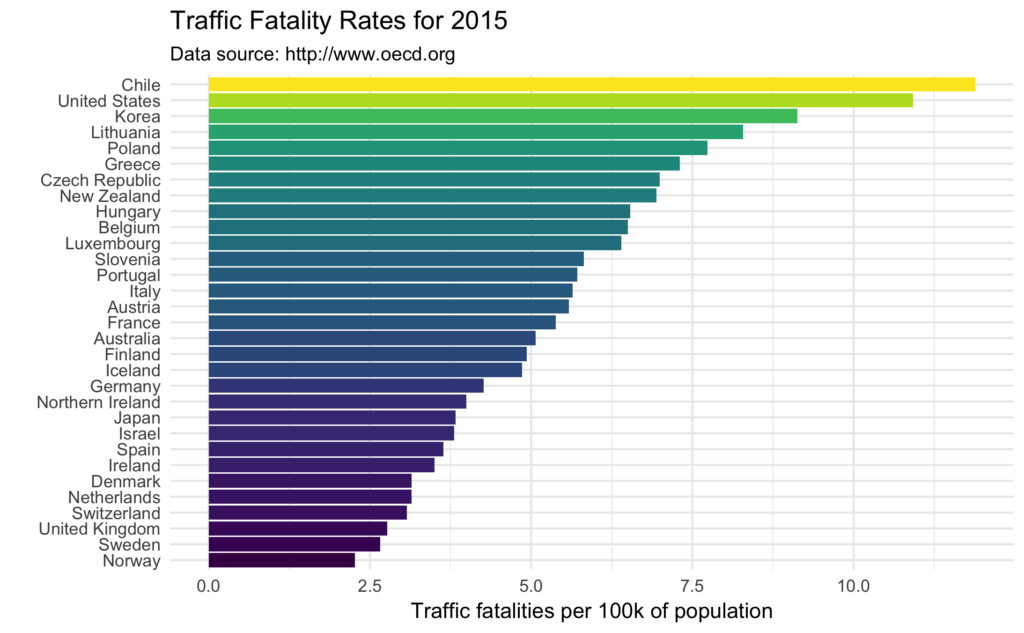

Driver distraction is one reason why the US lags the rest of the world in driving safety. The US has one of the worst safety records of any developed nation either by fatality per kilometer traveled or per hundred thousand people. A total of 37,461 people died in 2016 and 3,450 of these involved distractions ( https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812517)

Don’t drive

By not driving you avoid the temptation to drive distracted. Not driving also makes it possible to focus completely on work or social media that would not get full attention if done while driving—driving can undermine performance on negotiations and other business tasks. Another benefit of not driving is that public transport keeps you safe from distracted drivers.

Drivers: Use public transport, taxi, or automated vehicles

Designers: Make public transport options accessible and obvious

Related concepts: Dual-task performance decrement, Systems thinking, and Task re-design

Don’t engage in distractions

Because driving is literally a matter of life and death a total abstinence approach to distraction is warranted—no phone, no music, all focus. Unfortunately, even people with the best intentions succumb to habits and to salient events that demand attention, such a chime indicating an incoming message.

Driver: Use the power of pre-commitment and put the phone (tablet, laptop, … ) in the trunk or glove compartment.

Designer: Lockout interactions with a well-crafted “drive mode.” The drive mode should allow an easy override for passengers and should address common reasons why drivers might disable the mode, such as automatic notifications to people trying to make contact. Make the drive mode the default rather than require people to enable it: 70% of people have kept Apple’s drive mode activated.

Related concepts: Decision making and pre-commitment, Habits, Salience outweighs importance, Power of defaults

Don’t look away, don’t reach

Not surprisingly, keeping your eyes on the road and hands on the steering wheel is critical for safe driving. Reading, typing, and reaching are extremely dangerous. Surprisingly, people do this on a regular basis.

Driver: Use voice-based rather than visual-manual interactions with a phone. Use properly mounted or integrated systems and DO NOT reach for a phone that has slipped to the floor. Recognize that voice interactions are not risk-free, and that looking at the road does not mean you see the road, but looking away from the road guarantees you do not see it.

Designer: Drivers will tend to glance at any visual interface that accompanies the voice control and those glances contribute to crash risk.

Related concepts: Looked-but-did not see attentional lapses, Resource competition, and dual task decrement

Minimize long glances

Long glances are particularly dangerous and drivers tend to extend glances to complete sub-tasks, such as searching for an item on a screen or reading a phrase. Chronic multitaskers may be at a particular risk: they are less able to filter out irrelevant stimuli and are more confident in their multitasking ability.

Drivers: Recognize that long glances are extremely risky and that it is extremely hard to detect such glances when they are happening.

Designers: Minimize clutter and make items easily distinguishable to minimize visual search time. The salience of items should correspond to the likelihood the driver is searching for the item. Reading, typing, scrolling, and other tasks the require sustained glances should be avoided. Long tasks should be easy to interrupt and easy to resume.

Related concepts: Task switching and interruption management

Avoid inopportune glances and interactions

It is not just what you do but when you do it. Distraction depends on the combination of demand of the driving task and the demand of the non-driving task and so poorly timed distractions are particularly dangerous.

Drivers: Limit distracting interactions to low-demand, predictable situations, such as the beginning of a trip when you are stopped and before you start the engine. Avoid distractions during work zones, school zones, and dense high-speed traffic.

Designers: Interactions should be modulated by the driving context using information from the vehicle, which might include speed, surrounding traffic, and proximity to a turn. Likewise, vehicle automation that demands the driver be able to intervene in a moment without notice should not allow drivers’ attention to leave the road for a moment.

Related concepts: Workload and interruption management

Get feedback about driving and understand consequences

Drivers engage in dangerous behavior partly because of the don’t feel the risk and also because they feel that they are better than average drivers. Most 18-year-old males would it hard to believe they are more dangerous than their 85-year-old grandmother. People can drive badly for years but still feel that they are safe drivers because crashes are so rare and distraction might lead them to miss near-crash events.

Drivers: Use driver monitoring systems—including friends and family—to get feedback about driving to counteract the overconfidence that most of us suffer from. Passengers should consider their role to be that of a co-driver.

Designers: Particularly for teen and professional drivers, the feedback from driver monitoring systems should be part of a coaching system and an overall organizational response to distractions and safety. As with most training strategies, positive feedback works better than negative feedback.

Related concepts: Optimism bias and over-confidence, Feedback and training

Change the driving culture with shared feedback

Like many safety-related behaviors, technology alone will fail to address distraction. Changing norms, collective habits, and developing a strong safety culture is needed to fully address driver distraction. One indicator of safety culture is what gets counted: the US has no national database of all police-reported crashes, only fatal crashes get counted systematically.

Drivers: Adopt the attitude that killing someone with a poorly timed text is not an accident, but an avoidable tragedy. Rather than thinking about what has gone right in the past, think about what can go wrong in the future.

Designers: Consider the consequences of drawing drivers’ attention to an app, and the lives saved by guiding people away from distractions. Use technology to shape safer habits, such as guiding drivers to substitute safer activities for risky activities. Design policies, such as crash reporting systems, that record the role of distraction in crashes.

Related concepts: Safety culture, Habit, Metacognition and premortem analysis of decisions